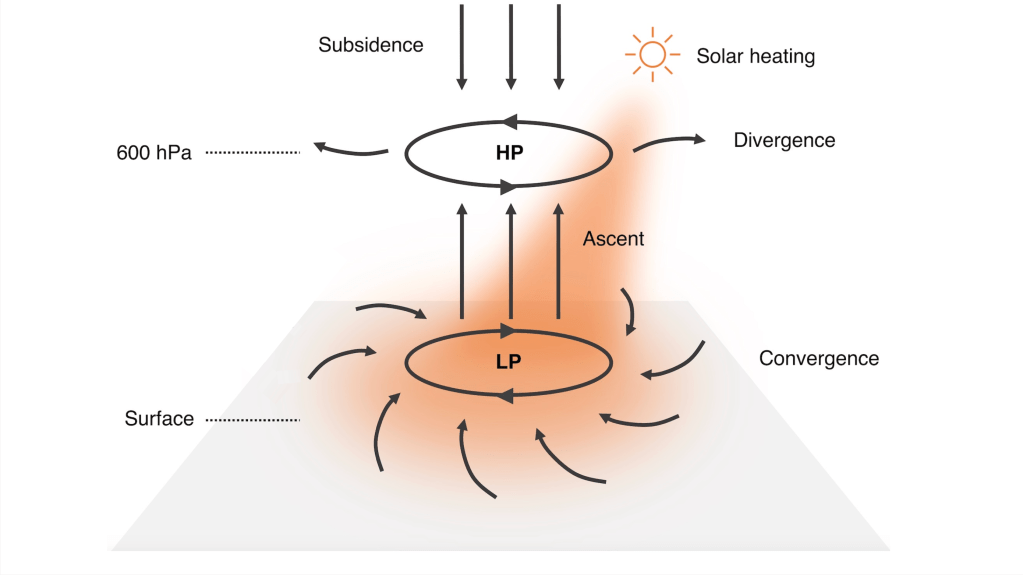

The Kalahari Heat Low is a feature of the lower atmospheric circulation that forms over the Kalahari Desert in austral summer (Attwood et al., 2024). Heat lows, or thermal lows, are key features of subtropical, desert climates, where intense solar heating driving dry, shallow convection causes a low-pressure system to develop (Rácz and Smith, 1999). As the surface heats up, air rises and the surface pressure decreases, generating convergence and cyclonic circulation at the surface (Figure 1). Above the heat low and beneath upper-level subsidence, a high-pressure system forms. In southern Africa this feature is the Botswana High (Driver and Reason, 2017). This keeps skies cloud-free, maintaining high surface solar radiation and acting as a cap on the dry convection associated with the heat low.

By influencing low-level pressure and humidity gradients, the heat low can affect winds and rainfall for hundreds of kilometres (Howard and Washington, 2019). The Kalahari Heat Low is the summer form of the southern African Heat Low, marking its southernmost position its seasonal cycle as it forms over central Namibia and northern South Africa (Munday and Washington, 2017). The low-pressure centre of the Kalahari Heat Low draws winds from the Indian Ocean via the Limpopo and Zambezi valleys, and sets up the hot, dry conditions of the Kalahari Desert (Spavins Hicks et al. 2021; Van Schalkwyk et al., 2023).

As the heat lows are driven by solar heating, they exhibit strong variability through the diurnal cycle. The minimum surface pressure is reached in the afternoon hours, following the daytime solar radiation maximum (Spengler and Smith, 2008). By contrast, low-level winds peak in the early morning once turbulence in the boundary layer has decreased and winds can accelerate (Rácz and Smith, 1999). This diurnal cycle is central to how the southern African heat low operates, hence the collection of high frequency observations (4-hourly radiosondes) throughout the observational campaign.

Recent research highlights the increasing frequency of strong heat lows over southern Africa in reanalysis data (Attwood et al., 2024). Southern Africa is expected to experience significantly reduced precipitation due to anthropogenic climate change, and this work indicates that the heat low may provide an important control on this regional trend. Despite this, projections of climate change in the region are uncertain as coupled models fail to capture the present-day rainfall climatology in many cases (Munday and Washington, 2017; Munday and Washington, 2019). Studies have suggested that the heat low may be a key missing piece of the puzzle, acting as a constraint on model ability to represent southern African climate and a determinant of subtropical rainfall onset (Dunning et al., 2018, Munday and Washington, 2018). Developing understandings of the heat low in observations is therefore a key step to build confidence in future trends of climate change.

Find out more about heat lows here.

References

Attwood, K., Washington, R. and Munday, C. (2024) ‘The Southern African Heat Low: Structure, Seasonal and Diurnal Variability, and Climatological Trends’, Journal of Climate, 1(aop). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-23-0522.1.

Driver, P. and Reason, C.J.C. (2017) ‘Variability in the Botswana High and its relationships with rainfall and temperature characteristics over southern Africa: VARIABILITY IN THE BOTSWANA HIGH AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN RAINFALL’, International journal of climatology, 37, pp. 570–581. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5022.

Dunning, C.M., Black, E. and Allan, R.P. (2018) ‘Later Wet Seasons with More Intense Rainfall over Africa under Future Climate Change’, Journal of Climate, 31(23), pp. 9719–9738. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0102.1.

Howard, E. and Washington, R. (2019) ‘Drylines in Southern Africa: Rediscovering the Congo Air Boundary’, Journal of Climate, 32(23), pp. 8223–8242. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0437.1.

Munday, C. and Washington, R. (2017) ‘Circulation controls on southern African precipitation in coupled models: The role of the Angola Low’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 122(2), pp. 861–877. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025736.

Munday, C. and Washington, R. (2018) ‘Systematic climate model rainfall biases over southern Africa: links to moisture circulation and topography’, Journal of Climate, 31, pp. 7533–7548. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0008.1.

Munday, C. and Washington, R. (2019) ‘Controls on the Diversity in Climate Model Projections of Early Summer Drying over Southern Africa’, Journal of Climate, 32(12), pp. 3707–3725. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0463.1.

Rácz, Z. and Smith, R.K. (1999) ‘The dynamics of heat lows’, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 125(553), pp. 225–252. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49712555313.

Van Schalkwyk, L. et al. (2023) ‘A Climatology of Dryline-Related Convection on the Western Plateau of Subtropical Southern Africa’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 128(18), p. e2023JD038966. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JD038966.

Spavins-Hicks, Z.D., Washington, R. and Munday, C. (2021) ‘The Limpopo Low-Level Jet: Mean Climatology and Role in Water Vapor Transport’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 126(16), p. e2020JD034364. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD034364.

Spengler, T. and Smith, R.K. (2008) ‘The dynamics of heat lows over flat terrain’, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 134(637), pp. 2157–2172. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.342.